April 14, 2016 PowerPoint Humanities Week 31 Jacob Lawrence Migration Series Worksheet Humanities Week 31 Jacob Lawrence Migration Series

Jacob Lawrence did not need to look far to find a heroic African American woman for this image of a solitary black laundress: his mother had spent long hours cleaning homes to support her children. Both she and the artist’s father had “come up” — a phrase used to indicate one of the most important events in African American history since Reconstruction: the migration of African Americans out of the rural South. This exodus was gathering strength at the time of World War I, and fundamentally altered the ethnic mix of New York City and great industrial centers such as Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh.

Lawrence was born in New Jersey, and settled with his mother and two siblings in Harlem at age thirteen. Harlem in the 1920s was rich in talent and creativity, and young Jacob, encouraged by well-known painter Charles Alston and sculptor Augusta Savage, dared to hope he could earn his living as an artist. “She [Augusta] was the first person to give me the idea of being an artist as a job,” Lawrence later recounted. “I always wanted to be an artist, but assumed I’d have to work in a laundry or something of that nature.”

Migration Series by Jacob Lawrence

The subject of the migration occurred to him in the mid-1930s. To prepare, Lawrence recalled anecdotes told by family and friends and spent months at the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library researching historical events. He was the first visual artist to engage this important topic, and he envisioned his work in a form unique to him: a painted and written narrative in the spirit of the West African Griot — a professional poet renowned as a repository of tradition and history.

The Migration Series was painted in tempera paint on small boards (here, twelve by eighteen inches) prepared with a shiny white glue base called gesso that emerges on the surface as tiny, textured dots. Lawrence, intent on constructing a seamless narrative, chose to work with a single hue at a time on all sixty panels. He used drawings only as a guide, painted with colors straight from the jar, and enlivened his compositions with vigorous brushstrokes that help further the movement of the story. The captions placed below each image are composed in a matter -of-fact tone; they were written first and are an integral part of the work, not simply an explanation of the image.

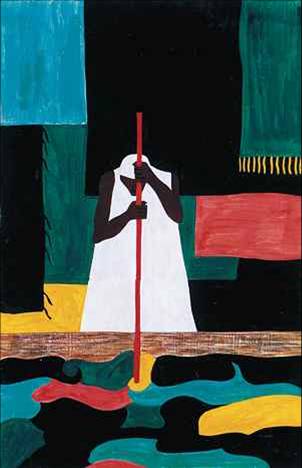

Lawrence often described the migration as “people on the move,” and his series begins and ends with crowds of people at a train station (a potent symbol for growth and change in American history). In the first panel, people stream away from the viewer through gates labeled “Chicago,” “New York,” and “St. Louis”; in the last one, they face us, still and silent, behind an empty track. The caption, which states, “And the migrants kept coming,” renders the message sent by the painting ambiguous and evocative. Are the migrants leaving us, or have they just arrived? What is our relationship to them? Lawrence also asks those questions of the laundress, who appears toward the end of the series. Her monumental, semipyramidal form, anchored between the brown vat containing a swirling pattern of orange, green, yellow, and black items and the overlapping rectangles of her completed work, is thrust toward us by her brilliant white smock. With head bent in physical and mental concentration, she wields an orange dolly, or washing stick, in a precise vertical: a powerful stabilizing force in the painting, and a visual metaphor for her strength and determination.

Migration Series by Jacob Lawrence

Lawrence showed The Migration Series in Harlem before being invited to bring it to a downtown setting that had previously displayed only the work of white artists. The exhibition received rave reviews and Lawrence’s acceptance by the art world and the public was confirmed when twenty-six of the panels were reproduced in Fortune magazine. Lawrence had intended the series to remain intact, but agreed to divide it between two museums, the even numbers going to the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, and the odd numbers to the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C

Have a good week. – Mrs. S